Data released in January solidified the notion that the economic growth momentum extended to the fourth quarter and possibly beyond. That strength has been anchored by a U.S. consumer that keeps spending at a very fast clip, even as income growth continues to moderate. Labor market metrics have kept the lukewarm low hiring/low firing picture in place, while measures of inflation remain above the Fed‘s 2% target. Of note, annual benchmark revisions to payrolls are expected to show that job growth slowed more sharply last year, and the delayed December personal consumption expenditures (“PCE”) report is expected to show that the Fed’s preferred annual rate of inflation gauge did not budge in 2025.

Economic Growth, Labor Market, and Inflation

While the Q4 GDP advance estimate release has been delayed to February 20th, revisions to Q3 GDP showed the economy expanded at a slightly higher than initially estimated 4.4% seasonally adjusted annualized rate (“SAAR”). Real consumer spending rose a solid 0.3% month-over-month (“mom”) in both October and November. Taken together, the two months of PCE data signaled that consumption patterns are normalizing after the tariff induced pull-forward in goods demand at the beginning of the year. That said, consumption gains continue to outpace income growth. The annual growth rate of real disposable income declined to 1.0% and the personal savings rate dropped to 3.5% in November – a more than 3-year low watermark.

While a few high-frequency indicators suggest that spending slowed in December, we estimate that Q4 spending will have risen a healthy 2.7% SAAR even if December spending comes in flat. However, we believe it is more likely that Q4 consumer spending growth will feature a 3%-handle and provide another boost to GDP growth. Case in point, most Q4 growth forecasts have been upgraded with the most recent Atlanta Fed GDP Now forecast tracking Q4 growth at 4.2% SAAR.(1) Looking ahead, tax relief from the Administration’s tax and spending reconciliation act is expected to provide additional support for consumer spending in the first half of 2026. Nevertheless, the tailwind from these tax refunds may be short-lived given that they will likely accrue to middle-to-upper-income households, which tend to have a lower marginal propensity to consume.

The final employment report of 2025 showed the labor market continued to soften gradually. Total payrolls rose 50k in December and 584k throughout 2025 – the lowest annual gain since 2003. Private payrolls also rose a modest 733k last year, representing less than half the 2024 gain, with the healthcare sector accounting for nearly all jobs created. Of note, the unemployment rate (“UER”) declined to 4.4% from a downward revised 4.5% level in November. However, the weakness in labor demand, as measured by the ratio of job openings per unemployed worker; the latest Conference Board's labor differential reading, and recent layoff announcements, predominantly in the tech sector, signal that the UER could come under further pressure in 2026.

Finally, while the December Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) was below expectations and matched a five-year low annual rate, the Producer Price Index (“PPI”) exceeded expectations. Moreover, components that feed into the PCE inflation calculation were relatively firm in both the CPI and PPI reports. Consequently, we expect core PCE to have risen just shy of 0.4% mom, failing to fully reflect the encouraging moderation in CPI inflation. Given methodological differences between the two inflation metrics, like the meaningfully higher weight assigned to shelter prices in the CPI, core PCE is expected to rise above Core CPI for the first time in several years (see panel 1). Additionally, with December core PCE expected to come in at approximately 3.0% year-over-year (“yoy”), the Fed will be unable to claim much “progress” on its preferred inflation measure for a fourth consecutive year.

Panel 1:

PCE Is Starting to Run Hotter Than CPI

Financial Markets

The first month of 2026 delivered no shortage of fireworks. January brought an unusually dense set of geopolitical, monetary, and fiscal headlines that, in prior cycles, would likely have driven sustained moves in U.S. interest rates. On the geopolitical front, markets absorbed the forceful removal of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and President Trump’s unconventional campaign to annex Greenland. On the monetary policy front, investors faced an unprecedented criminal investigation into a sitting Fed Chair, followed quickly by the announcement of Kevin Warsh as the nominee for the next Fed Chair. Fiscal policy also took center stage, as the Administration renewed its focus on supporting the housing market, culminating in a directive for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the “GSEs”) to purchase $200 billion of Agency MBS.

Yet the defining theme of the month was a clear disconnect between volatility and one-off moves across many asset classes and a U.S. Treasury market that remained largely unchanged. Treasury yields rose only modestly, 5 basis points (“bps”) on average across the curve, and ended the month well within the ranges that have prevailed for several months. Therein, implied volatility in U.S. rates continued to decline, approaching historically low levels.

This calm in rates reflects a relatively narrow set of near-term policy outcomes. Fiscal policy has taken a supportive tone, with a clear emphasis on keeping long-end interest rates contained. Monetary policy appears close to neutral, with limited justification for renewed tightening and only modest scope for cuts. Positioning across rates markets has remained relatively clean, as ongoing headline risk has discouraged large directional bets. And funding markets have reinforced this stability, with the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (“SOFR”) and broader money markets continuing to trade in an orderly fashion, supported by the Fed’s balance sheet backstop.

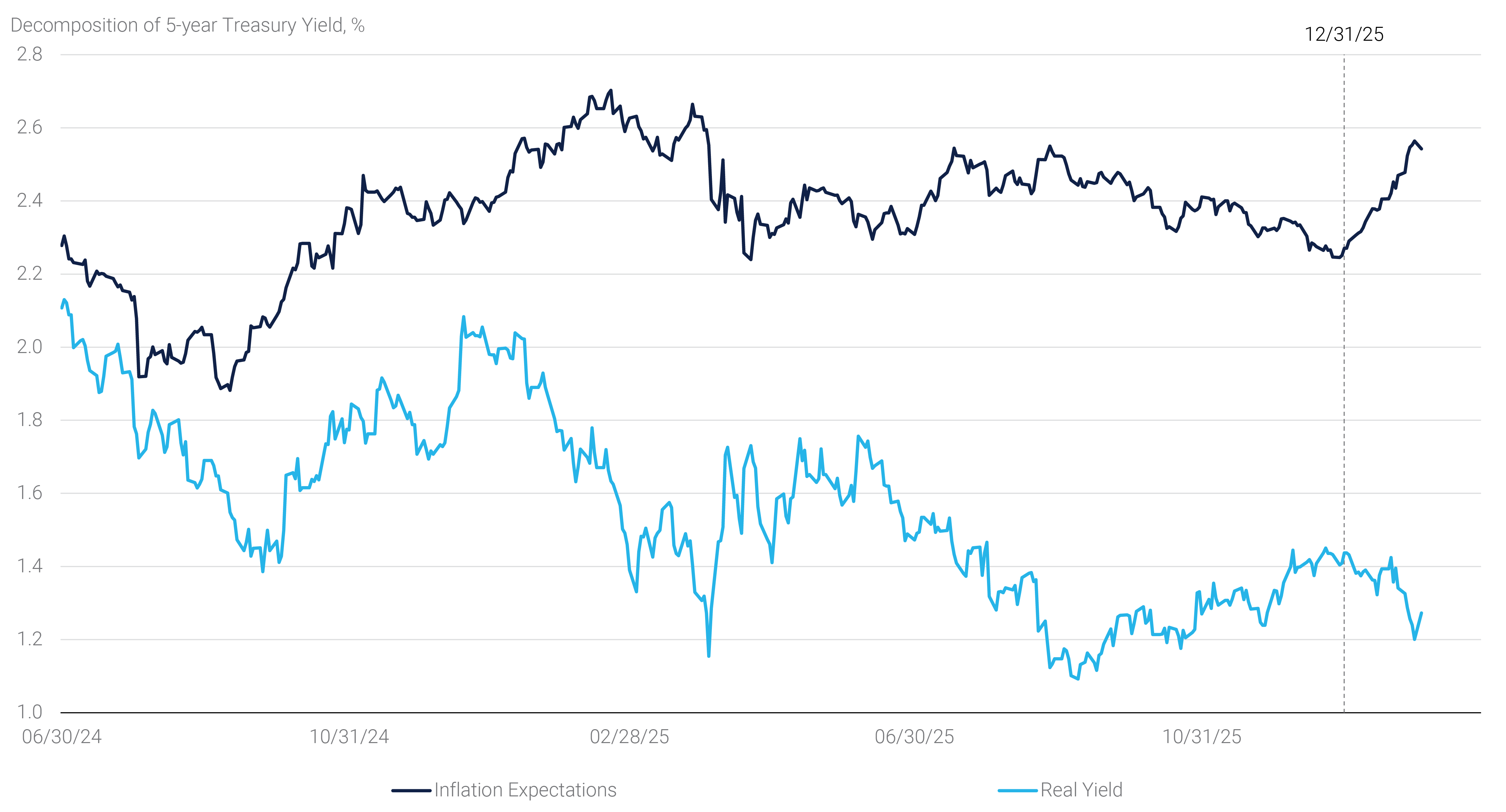

Even so, the stability in nominal rates masked meaningful divergence beneath the surface. Inflation expectations and real rates moved sharply in opposite directions during the month, leaving headline yields little changed

(see panel 2). For example, 5-year inflation breakevens rose more than 30 bps, offset by a comparable move in real rate pricing. This repricing likely reflects the accumulation of headline risks, including higher energy prices, a weaker U.S. dollar, and still-firm inflation data that we can now confirm persisted through the fourth quarter.

Panel 2:

Limited Nominal Yield Changes Disguised Volatility in Its Components

Outside of interest rates, volatility was far more pronounced across other asset classes. Equity markets experienced sharp single-stock moves, particularly among large-cap technology names, while commodities saw significant swings. Silver, after rallying 148% in 2025, climbed another 61% year-to-date before plunging roughly 26% on the final trading day of January. Oil prices also moved higher, ending the month up roughly 15% despite the notable developments in Venezuela. Currency markets showed similar instability, as the U.S. dollar fell as much as 3% peak to trough in January, breaking through multi-year lows, while sharp swings in the Japanese Yen highlighted the unsettled global backdrop. Debt markets, by contrast, largely shrugged off the turbulence. Corporate credit performed well in January, with the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Corporate Bond Index generating a 0.34% excess return during the month.

Agency MBS

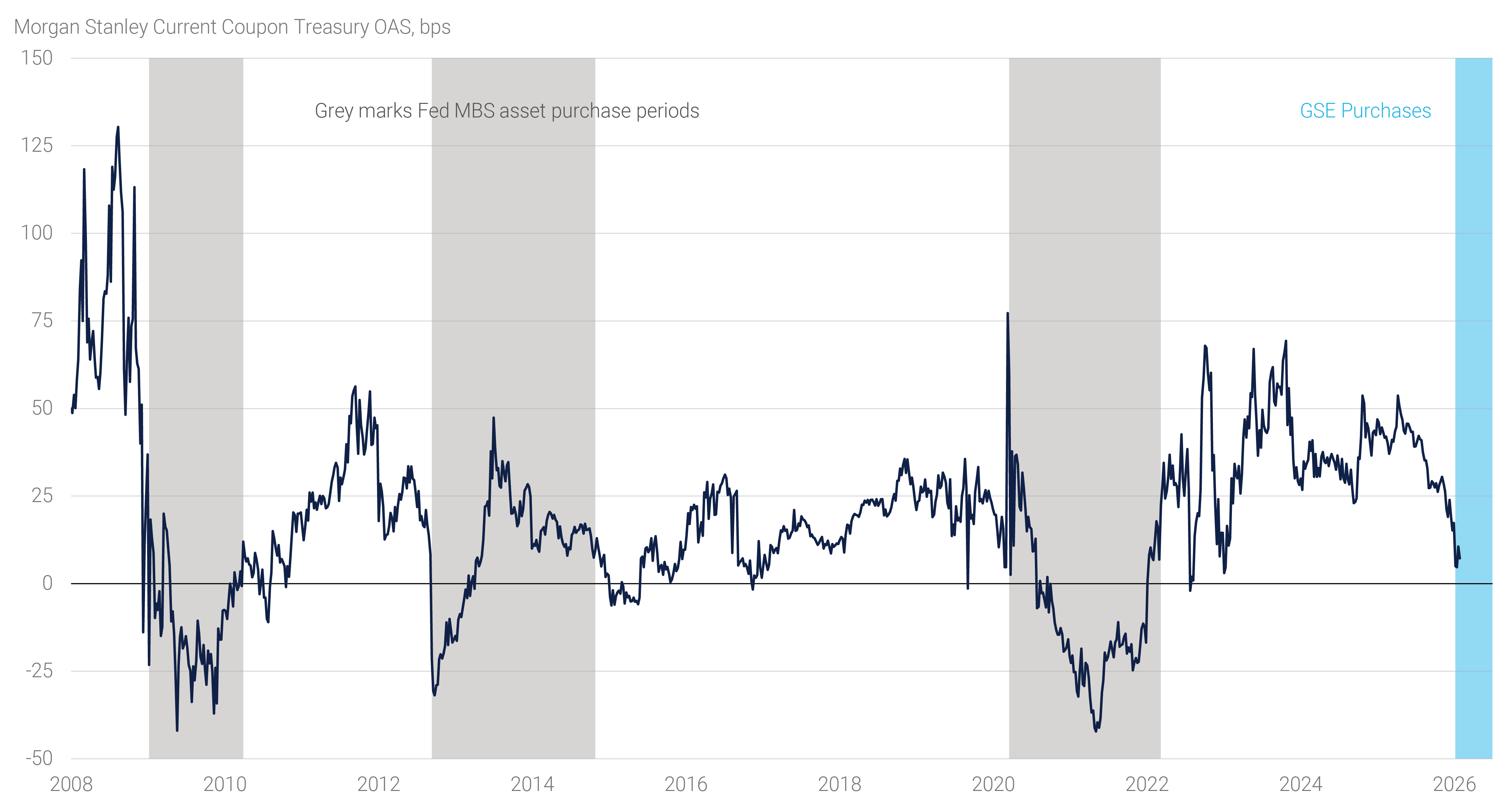

For mortgage investors, January’s most consequential development was the Administration’s intervention in the Agency MBS market. President Trump’s announcement directing the GSEs to purchase $200 billion of Agency MBS marked a clear shift in tone and triggered an immediate repricing in mortgage spreads. Treasury option-adjusted spreads (“OAS”) tightened sharply, briefly touching single digit levels, before settling into a new post-announcement range roughly 10 bps tighter than pre-announcement levels (see panel 3). Intermediate and lower coupon spreads outperformed their higher coupon counterparts, while higher coupon generic collateral faced elevated policy risk. Mortgage rates briefly touched 6%, spurring a renewed pickup in refinancing application activity.

Panel 3:

MBS Spreads Tightened Into the GSE Announcement

These dynamics also had implications for interest rate swap spreads. Historically, large GSE MBS purchases have been accompanied by hedging activity of paying fixed in swaps which tends to widen swap spreads. Consistent with that history, swap spreads initially widened following the announcement. However, as markets digested a wide range of competing headlines over the remainder of the month, swap spreads ultimately ended January tighter across the curve, highlighting how swaps remain a volatile pocket within the rates complex.

In a month defined by extraordinary headlines and uneven cross-asset volatility, the relative stability of U.S. rates and the policy-driven repricing of Agency MBS stood out as the most important developments for mortgage portfolios. January reinforced a key theme entering 2026: contained rate volatility can coexist with significant turbulence elsewhere, while targeted fiscal actions can still produce powerful, localized market effects when policy intent is relatively clear.

The Administration's GSE MBS Purchase Announcement

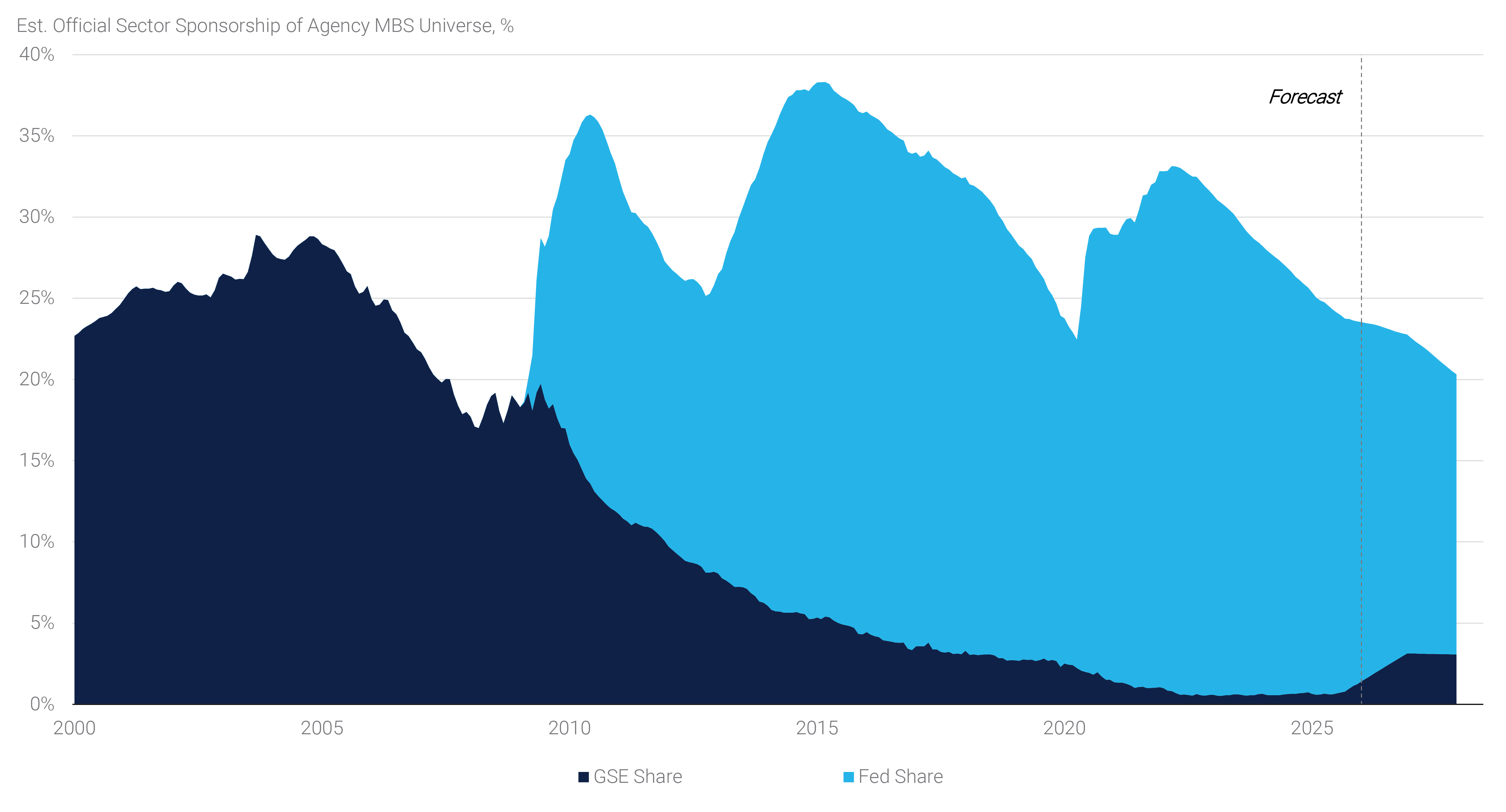

The White House’s increased focus on affordability and early January announcement instructing the GSEs to buy $200 billion in mortgage bonds has reintroduced official sector support for Agency MBS for the first time since the Fed began reducing its securities portfolio holdings in June 2022. Before the 2008 Financial Crisis (the “GFC”), the GSEs were economic buyers and sellers of mortgages for their retained portfolios, which reached more than $1.5 trillion combined at their peak. When the GSEs were placed in conservatorship in 2008, the agreement reached between the Federal Housing Finance Agency (“FHFA”) and the U.S. Treasury on capital injections into the GSEs also mandated that they run down their retained portfolios annually, which are each capped at $225 billion today.(2)

As the GSEs began to reduce their retained portfolios in 2008, the Fed announced MBS purchases to improve financial conditions and support mortgage and housing markets. Over time, the central bank amassed as much as $2.7 trillion of MBS on its balance sheet, quickly bringing official sector sponsorship to all-time highs. While showing ebbs and flow over time, official sector sponsorship had generally fallen to close to post-GFC lows in recent months. The announced GSE purchases will essentially offset Fed portfolio runoff in 2026, though official sector holdings should continue to decline as a share of the universe after this year outside of future changes (see panel 4).

Panel 4:

Official Sector Sponsorship

President Trump’s announcement of GSE portfolio purchases tightened mortgage spreads, driving primary mortgage rates approximately 15 bps lower to around 6%. Conceptually, consumer mortgage rates can be thought of as the sum of i) the Treasury rate, ii) a spread that compensates MBS holders for mortgage-specific risks such as prepayments, and iii) the primary-secondary spread.(3) Assuming the latter is largely constant over time, one would ideally affect both the Treasury rate and mortgage spreads to sustainably lower consumer mortgage rates. Of note, historically, GSE purchases have primarily impacted mortgage spreads while Fed purchases have impacted both mortgage spreads and Treasury rates due to the important distinction between the programs.

Because of the nature of monetary policy, the Fed is not required to fund or hedge its purchases of MBS and is able to devote theoretically unlimited balance sheet to bring down mortgage rates and remove fixed income supply from private investors. The GSEs, on the other hand, have historically needed to hedge the interest rate risk of mortgage purchases and raise debt to fund them. Finally, the Fed’s quantitative easing program led to increased deposits at banks, which created additional MBS demand from banks, while we believe the GSE purchases are unlikely to do so.

The size of the purchase program is also an important factor impacting the mortgage rate. There are three likely ways in which the GSE purchase program could affect spreads:

- Flow effect: where the demand from the GSEs push spreads tighter. This ends when the GSEs stop purchasing MBS,

- Stock effect: the total holding of Agency MBS creates scarcity value for the asset, and

- Reduced tail risk: making the asset more attractive to other investors by decreasing the downside risk of owning the asset.

While notable, the size of the announced $200 billion in MBS purchases is small relative to the size of the $9.2 trillion Agency MBS market,(4) so unless the program is expanded significantly, the flow effect is likely to dissipate quickly and the stock effect might be quite limited. However, the GSEs could maximize the impact of purchases by stepping into the market when spreads are wide and selling when spreads are tight, thereby narrowing mortgage spread moves, reducing MBS volatility, and potentially improving the GSEs’ return on equity (“ROE”). This should attract other MBS investors into the market as volatility of MBS returns is diminished, leading to lower mortgage rates over time.

Indeed, the GSEs’ purchase strategy will differ significantly depending on whether they act as spread stabilizers or just as a one-time buyer of $200 billion in MBS. In order to act as a spread stabilizer, the GSEs will likely have to be relative value buyers of MBS across the coupon stack and across conventional(5) and Ginnie Mae MBS. Should the GSEs refrain from purchasing coupons with attractive cash flows, market participants could interpret the GSE’s reluctance as an indication of these securities containing potential policy risks. Similarly, a focus on conventional purchases alone could result in unintended consequences for Ginnie Mae securities and underlying loan originations. Moreover, to act as a spread stabilizer, they likely will have to hedge their purchases, or they are more of a yield buyer similar to traditional bank or overseas investors.

Finally, there has been a great deal of discussion regarding other potential policy announcements intended to address housing affordability, the likelihood and the timing of such are highly uncertain. The more plausible potential policy announcements would fall within the FHFA and the Administration’s jurisdiction and will likely be designed to have limited negative impact on mortgage spreads or GSE ROEs. Some of those initiatives could include changes, at the margins, to GSE loan level pricing adjustments(6) and guarantee fees as well as Federal Housing Administration mortgage insurance premiums ideally targeted at purchase borrowers, or lifting the GSEs’ retained portfolio caps further. For the time being, FHFA Director Pulte’s social media post in late January that the GSEs’ mortgage purchases will not exceed $200 billion has quelled some speculation that GSE retained portfolio caps could be further increased. Outside of specific measures to lower the mortgage spreads, we believe that the Administration should continue its focus on the stability of Treasury yields, as lower market volatility given a high degree of stability in Treasury yields has done more to lower the mortgage rate than any purchase announcement.